The Flint water crisis is the result of a long chain of decisions and actions, culminating in a colossal failure by a state regulatory agency. But the first decision on the chain, the match that lit the fuse, was the decision by the Detroit Water and Sewer Department to terminate Flint’s contract two years before Flint’s new pipeline would be completed.

The Flint water crisis is the result of a long chain of decisions and actions, culminating in a colossal failure by a state regulatory agency. But the first decision on the chain, the match that lit the fuse, was the decision by the Detroit Water and Sewer Department to terminate Flint’s contract two years before Flint’s new pipeline would be completed.

The paper trail – or absence thereof – suggests that decision may have been made illegally.

The notice of termination was delivered to Flint on April 17, 2013 – one day after Flint Emergency Manager Ed Kurtz signed the agreement with Karegnondi Water Authority, and a week after Flint’s City Council endorsed that agreement.

That termination is underscored by this resolution by the Detroit water board, adopted on Feb. 12, 2014. Its fourth “whereas:” “on April 16, 2013 the Board provided a one year notice of intent to terminate service under the December 25, 1965 agreement …”

But there is no record of an action by that board to give notice of termination of the contract. All the Detroit Water Board’s meeting minutes, agendas and director’s reports are available online. One would think – and the resolution noted above would confirm – that at a meeting somewhere in Feburary, March or April of 2013, the board discussed and voted upon a termination of Flint’s contact if, indeed, it signed with KWA.

There is no record that any such discussion, or vote, took place. Neither is there, going back well into 2012, any record of discussion or a vote to authorizing the director to terminate the contract.

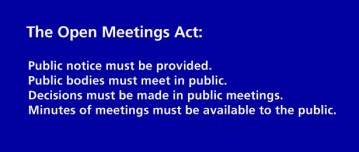

If the resolution is true – that DWSD’s board took that action – it appears to have happened in violation of the Michigan Open Meetings Act.

Backing Flint into a corner

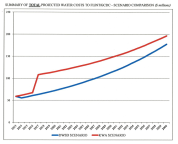

The media chasing this story have been buzzing the last week over the last-ditch offer DWSD made to Flint in April of 2013 – just weeks before Flint’s Council voted to join KWA and Kurtz signed the agreement. Detroit was offering Flint – and the KWA – a 20-percent reduction in its water rates to lock in a 30-year contract. It even had a nice little chart (left) showing DWSD’s projections that would save Flint millions of dollars over the KWA’s planned Lake Huron pipeline.

(left) showing DWSD’s projections that would save Flint millions of dollars over the KWA’s planned Lake Huron pipeline.

Except, as Genesee County Drain Commissioner Jeff Wright – the driving force behind KWA – told Jim Lynch of the Detroit News, Detroit would not guarantee to lock those rates in for more than one year. Which makes the projections pretty meaningless, given Detroit’s 10-year history of giving Flint an average 6.3-percent rate increase each year.

After a long history with Detroit, Flint may have felt it wise to turn the offer down.

I have said that Detroit – knowing their departing customer would not be able to draw from its new source for at least two to three years – gave them the one-year termination notice for one or both of two reasons. Spite. Or to back Flint into a corner so it could jack up its price for the interim supply.

We don’t know if the first is true; the News’ Lynch was planning to interview DWSD director Sue McCormick. But we know from the record that the second part is.

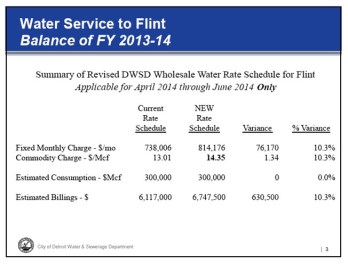

On April 15, 2014, Detroit made its final offer for interim water to Flint. After 10 years of an average 6.3-percent hike – and less than a year after offering more than a 40-percent reduction – they demanded a 10-percent increase.

On April 15, 2014, Detroit made its final offer for interim water to Flint. After 10 years of an average 6.3-percent hike – and less than a year after offering more than a 40-percent reduction – they demanded a 10-percent increase.

And that rate was only for the remainder of Flint’s fiscal year – from the time the previous contract termination took effect, April 17, 2014 (two days!) until June 30, 2014. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to assume another increase would follow for 2014-15.

I get that the scale of the 2013 offer, which included other communities committed to KWA, and the interim supply for Flint makes a big difference in how you set rates. But part of the problem here is that Detroit has a great deal of excess capacity: high supply, low demand. This is one of those areas where the law of supply and demand, apparently, does not apply.

Detroit’s offer was accompanied by the resolution noted above. It’s not hard to read between the lines: “We took care of you for 35 years, and then some. But you cheated on us, so we’re booting you out. You can live here until you move into your new home, but it will cost you.”

When Flint got T-boned

The Detroit decision looms large in the Flint tragedy, but no larger than a number of other decisions that led Flint to draw its water from the river. The fact that this one may have skirted the law puts it in a different light – and, perhaps, a different class. Perhaps that’s why there are people working very hard to make sure DWSD’s role fades into the background. Either way, it doesn’t change where the major part of the accountability for this tragedy lies.

You’re out of milk and go to the store. The checkout clerk is horribly slow, and it takes longer than you’d hoped to get out. Your spouse calls and asks you to stop at the pharmacy.

As you leave the pharmacy, you stop to wait for a pedestrian, an elderly lady who takes what seems like forever to cross. A few blocks later, a work crew has the street closed, and you follow the marked detour.

The detour takes you to a light, which is green. As you pass through, a car blasts through the red light and T-bones you.

Whose fault is the crash?

After all, a number of things happened to put you in that intersection at the exact moment the other driver came through. Is the accident the fault of the work crew? The old lady crossing the street? Your spouse? The slow clerk? Whoever drank the last of the milk?

The decision to draw water from the Flint River – made, according to evidence, by either then-Flint-EM Darnell Earley or then-State-Treasurer Andy Dillon – was a critical one. But so was the decision that led to it – Detroit’s to terminate the contract. So was the decision that led to that – Flint’s to join KWA.

Regardless of the decisions that led to that intersection of water and lead, though, the guy who blew the red light is the DEQ.

It maintained a culture – likely informed by the philosophy of its director and its governor – that “government regulation” is a bad thing, that DEQ should take a minimalist approach to compliance. It issued a permit to begin treating Flint River water that did not specify the right protocols. It arrogantly impressed upon Flint its own mistaken interpretation of the Lead and Copper Rule. It disparaged and discredited anyone who pointed to the increasingly apparent problems.

It’s amazing, in some ways, because the kind of arrogance we’ve seen here is usually practiced by people who are good at what they do. This combination of this level of incompetence with this kind of hubris is unusual – and tragic.

DEQ ran the red light. Detroit merely sent us to the store. But they may not have followed state law in doing so.

Nice article. Still your question is not at the root of the problem in my opinion.

Flint and Detroit are both cities of minorities that have had to manage a down turn. Their performances turned a down turn into a death spiral. Looking for one meeting, one decision, one anything as you also have seen is going to miss more than hit the point.

I’ve written at length about the broader picture that left Flint, Detroit (and Saginaw, Pontiac, Benton Harbor and many others) with high minority populations, high rates of poverty and disinvestment and inadequate financial resources. Our current Republican administration and legislature have doubled down on some of those root causes, but many of them can be traced back to local, state and federal policies, both D and R, to the end of WWII. The reluctance of local elected officials to make tough choices that are unpopular with voters accelerated that decline; in the case of Detroit — and Flint to a much lesser degree — incompetence and/or outright corruption played a role as well.

It still doesn’t change the fact that if the DEQ had done its job — and then not be dinks about the fact they hadn’t — none of this would have happened. Period.

That is certainly the truth. The DEQ has long acted as their own entity unto their self. They don’t even play well with other state groups.

They have shot themselves in the head on this one and will have to face the public and governmental bodies over their actions, which are also inaction.

Where your writing on poverty in those cities? I’m doing an article on race and how those policies contributed to the water crisis (though I agree, this is mainly the DEQ’s fault).

What was the EPA’s role in this? There was a high level resignation there. Was there or should there be interaction between state and federal on this?

There was. One EPA guy pointed to problems, but DEQ blew him off as a rogue employee, and EPA staff didn’t follow through.

Greg, I think you’re overlooking an important possibility in your analysis. The Open Meetings Act defines decisions made by public bodies as anything that would require a vote by the body. But if Kevyn Orr, who was EM for Detroit at the time, simply exercised the Department’s power to serve the termination notice, then this action would have fallen outside the Open Meetings Act because no vote was required.

I suspect that the Detroit EM was the one who made the decision to serve the notice, and the person who wrote the “whereas:” resolution one year later the simply -presumed- that the Board voted on a resolution without looking up the actual history.

Hey Greg – were you ever able to find out anything else about who authorized the termination?